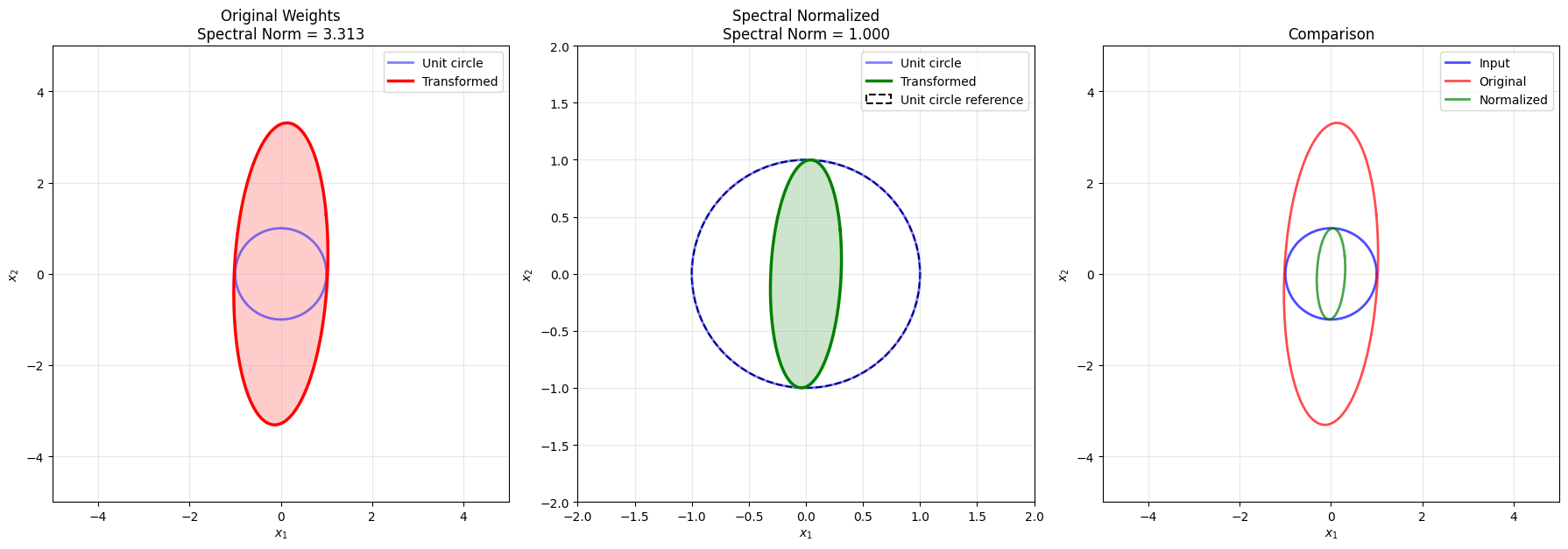

# Create an interesting transformation matrix

# Mix of rotation and stretching

np.random.seed(42)

A = np.array([[2.0, 0.5],

[0.3, 1.0]])

print("Transformation matrix A:")

print(A)

# Compute SVD

U, singular_values, Vt = np.linalg.svd(A)

print(f"\nSingular values: {singular_values}")

print(f"Spectral norm (max singular value): {singular_values[0]:.4f}")

print(f"Condition number: {singular_values[0]/singular_values[1]:.4f}")

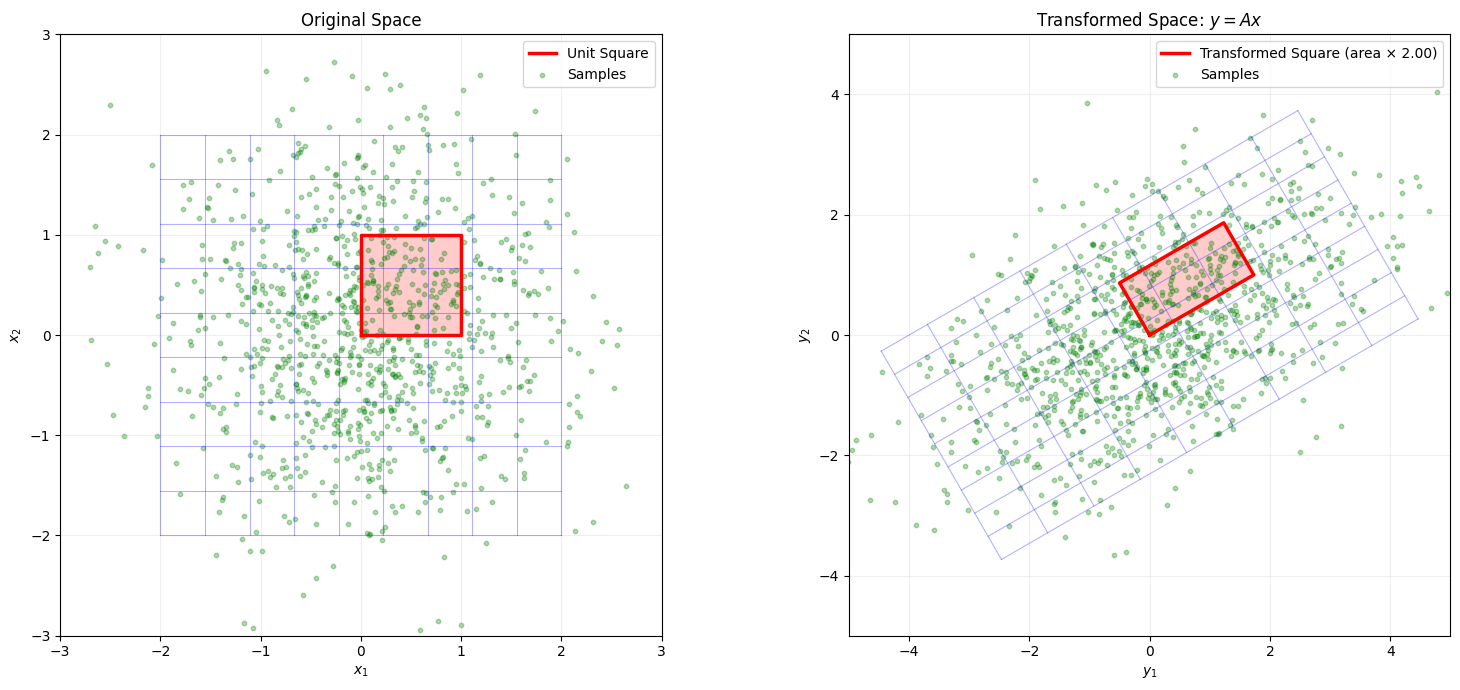

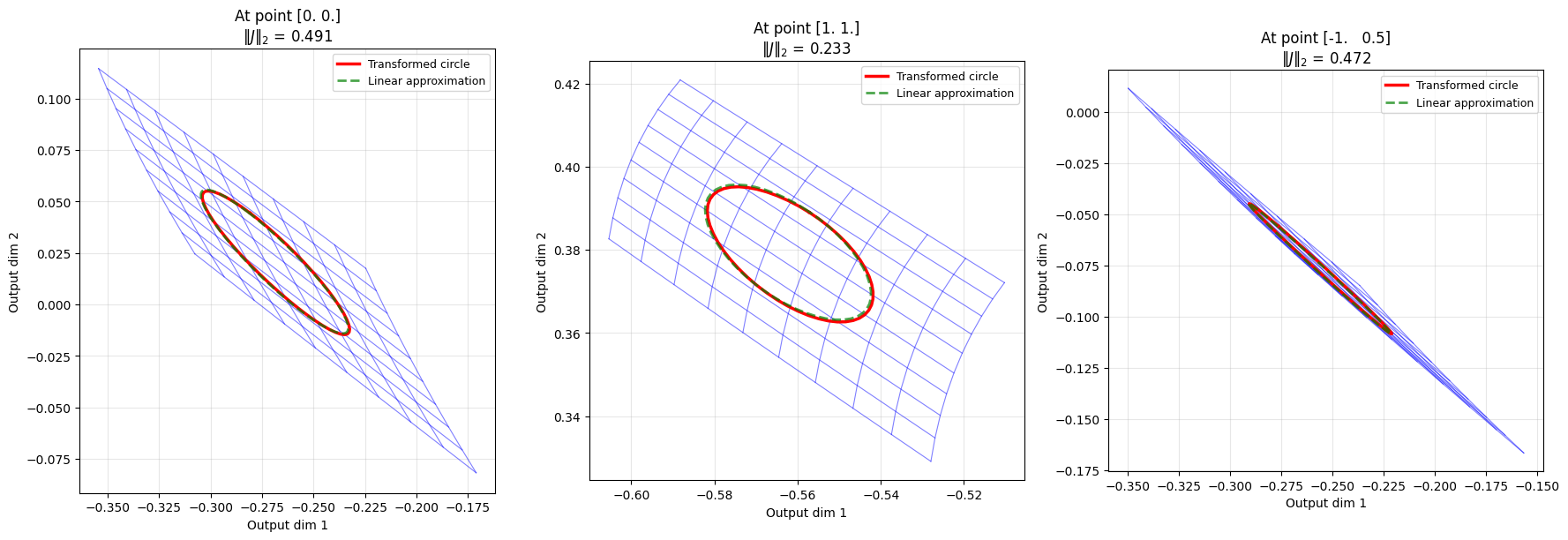

# Create a grid of points

n_grid = 15

x = np.linspace(-1, 1, n_grid)

y = np.linspace(-1, 1, n_grid)

X, Y = np.meshgrid(x, y)

# Create points on grid

points = np.stack([X.ravel(), Y.ravel()], axis=0)

# Apply transformation

transformed_points = A @ points

# Reshape back to grid

X_trans = transformed_points[0, :].reshape(X.shape)

Y_trans = transformed_points[1, :].reshape(Y.shape)

# Create visualization

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(16, 7))

# Left: Original grid

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(121, aspect='equal')

for i in range(n_grid):

ax1.plot(X[i, :], Y[i, :], 'b-', alpha=0.5, linewidth=1)

ax1.plot(X[:, i], Y[:, i], 'b-', alpha=0.5, linewidth=1)

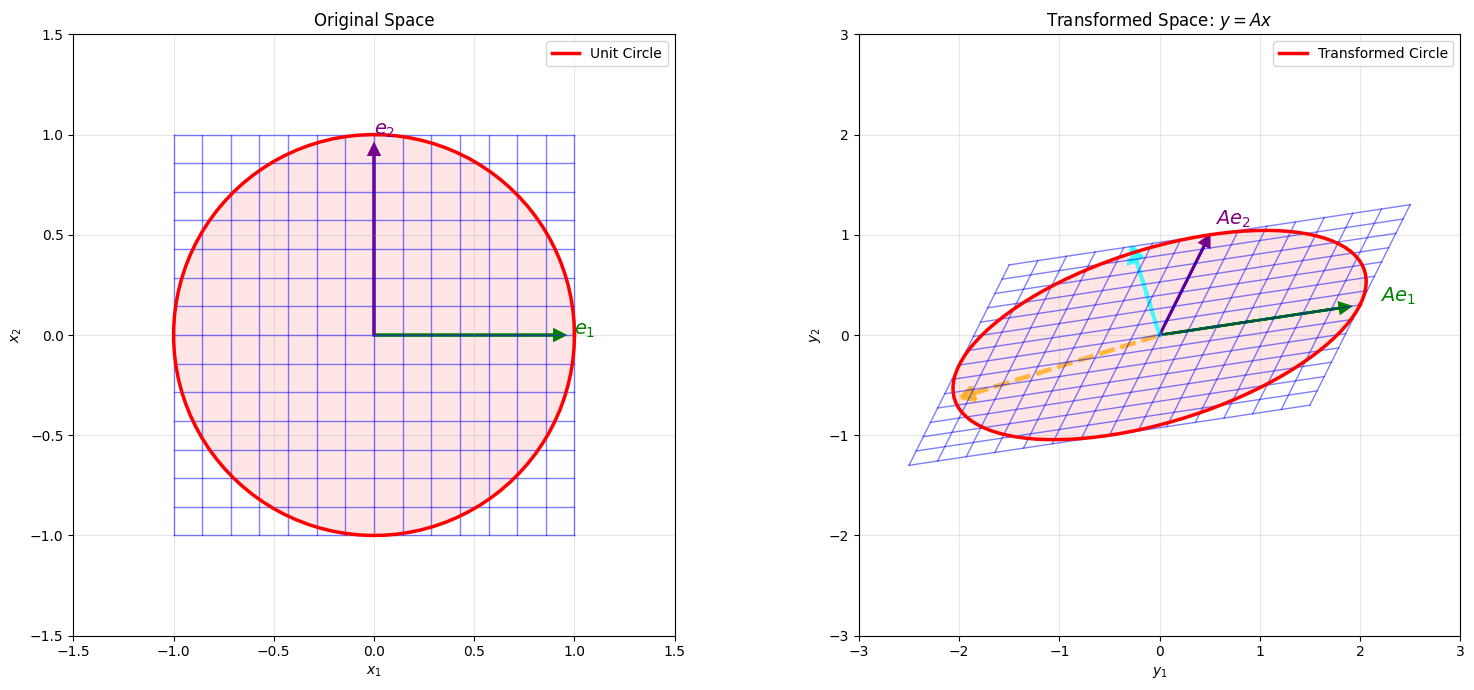

# Draw unit circle

theta = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 100)

unit_circle_x = np.cos(theta)

unit_circle_y = np.sin(theta)

ax1.plot(unit_circle_x, unit_circle_y, 'r-', linewidth=2.5, label='Unit Circle')

ax1.fill(unit_circle_x, unit_circle_y, 'red', alpha=0.1)

# Draw coordinate axes

ax1.arrow(0, 0, 0.9, 0, head_width=0.05, head_length=0.05, fc='green', ec='green', linewidth=2)

ax1.arrow(0, 0, 0, 0.9, head_width=0.05, head_length=0.05, fc='purple', ec='purple', linewidth=2)

ax1.text(1.0, 0, '$e_1$', fontsize=14, color='green', fontweight='bold')

ax1.text(0, 1.0, '$e_2$', fontsize=14, color='purple', fontweight='bold')

ax1.set_xlim(-1.5, 1.5)

ax1.set_ylim(-1.5, 1.5)

ax1.set_xlabel('$x_1$')

ax1.set_ylabel('$x_2$')

ax1.set_title('Original Space')

ax1.legend()

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Right: Transformed grid

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(122, aspect='equal')

for i in range(n_grid):

ax2.plot(X_trans[i, :], Y_trans[i, :], 'b-', alpha=0.5, linewidth=1)

ax2.plot(X_trans[:, i], Y_trans[:, i], 'b-', alpha=0.5, linewidth=1)

# Transform unit circle -> ellipse

ellipse_points = A @ np.stack([unit_circle_x, unit_circle_y])

ax2.plot(ellipse_points[0, :], ellipse_points[1, :], 'r-', linewidth=2.5,

label='Transformed Circle')

ax2.fill(ellipse_points[0, :], ellipse_points[1, :], 'red', alpha=0.1)

# Draw transformed coordinate axes

e1_trans = A @ np.array([1, 0])

e2_trans = A @ np.array([0, 1])

ax2.arrow(0, 0, e1_trans[0]*0.9, e1_trans[1]*0.9,

head_width=0.1, head_length=0.1, fc='green', ec='green', linewidth=2)

ax2.arrow(0, 0, e2_trans[0]*0.9, e2_trans[1]*0.9,

head_width=0.1, head_length=0.1, fc='purple', ec='purple', linewidth=2)

ax2.text(e1_trans[0]*1.1, e1_trans[1]*1.1, '$Ae_1$',

fontsize=14, color='green', fontweight='bold')

ax2.text(e2_trans[0]*1.1, e2_trans[1]*1.1, '$Ae_2$',

fontsize=14, color='purple', fontweight='bold')

# Draw singular vectors

# Right singular vectors (V) point in direction of maximum stretch

# Left singular vectors (U) point in direction of output

v1 = Vt[0, :] # Direction of max stretch in input

v2 = Vt[1, :] # Direction of min stretch in input

u1 = U[:, 0] # Direction in output

u2 = U[:, 1]

# Draw principal directions in transformed space

sigma1_vec = singular_values[0] * u1

sigma2_vec = singular_values[1] * u2

ax2.arrow(0, 0, sigma1_vec[0]*0.9, sigma1_vec[1]*0.9,

head_width=0.15, head_length=0.15, fc='orange', ec='orange',

linewidth=3, alpha=0.7, linestyle='--')

ax2.arrow(0, 0, sigma2_vec[0]*0.9, sigma2_vec[1]*0.9,

head_width=0.15, head_length=0.15, fc='cyan', ec='cyan',

linewidth=3, alpha=0.7, linestyle='--')

ax2.set_xlim(-3, 3)

ax2.set_ylim(-3, 3)

ax2.set_xlabel('$y_1$')

ax2.set_ylabel('$y_2$')

ax2.set_title('Transformed Space: $y = Ax$')

ax2.legend()

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()