# Conditional affine coupling layer

class ConditionalAffineCoupling(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dim: int, cond_dim: int, hidden_dim: int, mask: torch.Tensor):

super().__init__()

self.dim = dim

self.register_buffer('mask', mask)

# Condition on both masked input and label

self.scale_net = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(dim + cond_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, dim)

)

self.translate_net = nn.Sequential(

nn.Linear(dim + cond_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, hidden_dim),

nn.ReLU(),

nn.Linear(hidden_dim, dim)

)

nn.init.zeros_(self.scale_net[-1].weight)

nn.init.zeros_(self.scale_net[-1].bias)

nn.init.zeros_(self.translate_net[-1].weight)

nn.init.zeros_(self.translate_net[-1].bias)

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor, y: torch.Tensor) -> Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

x_masked = x * self.mask

xy = torch.cat([x_masked, y], dim=1)

s = self.scale_net(xy) * (1 - self.mask)

t = self.translate_net(xy) * (1 - self.mask)

s = torch.tanh(s)

out = x_masked + (1 - self.mask) * (x * torch.exp(s) + t)

log_det = ((1 - self.mask) * s).sum(dim=1)

return out, log_det

def inverse(self, y_out: torch.Tensor, y_cond: torch.Tensor) -> Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

y_masked = y_out * self.mask

yc = torch.cat([y_masked, y_cond], dim=1)

s = self.scale_net(yc) * (1 - self.mask)

t = self.translate_net(yc) * (1 - self.mask)

s = torch.tanh(s)

x = y_masked + (1 - self.mask) * ((y_out - t) * torch.exp(-s))

log_det = -((1 - self.mask) * s).sum(dim=1)

return x, log_det

# Conditional RealNVP

class ConditionalRealNVP(nn.Module):

def __init__(self, dim: int = 2, cond_dim: int = 8, hidden_dim: int = 128, n_layers: int = 6):

super().__init__()

masks = []

for i in range(n_layers):

mask = torch.tensor([1.0, 0.0]) if i % 2 == 0 else torch.tensor([0.0, 1.0])

masks.append(mask)

self.layers = nn.ModuleList([

ConditionalAffineCoupling(dim=dim, cond_dim=cond_dim, hidden_dim=hidden_dim, mask=mask)

for mask in masks

])

def forward(self, x: torch.Tensor, y: torch.Tensor) -> Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

log_det_total = torch.zeros(x.shape[0], device=x.device)

z = x

for layer in self.layers:

z, log_det = layer(z, y)

log_det_total = log_det_total + log_det

return z, log_det_total

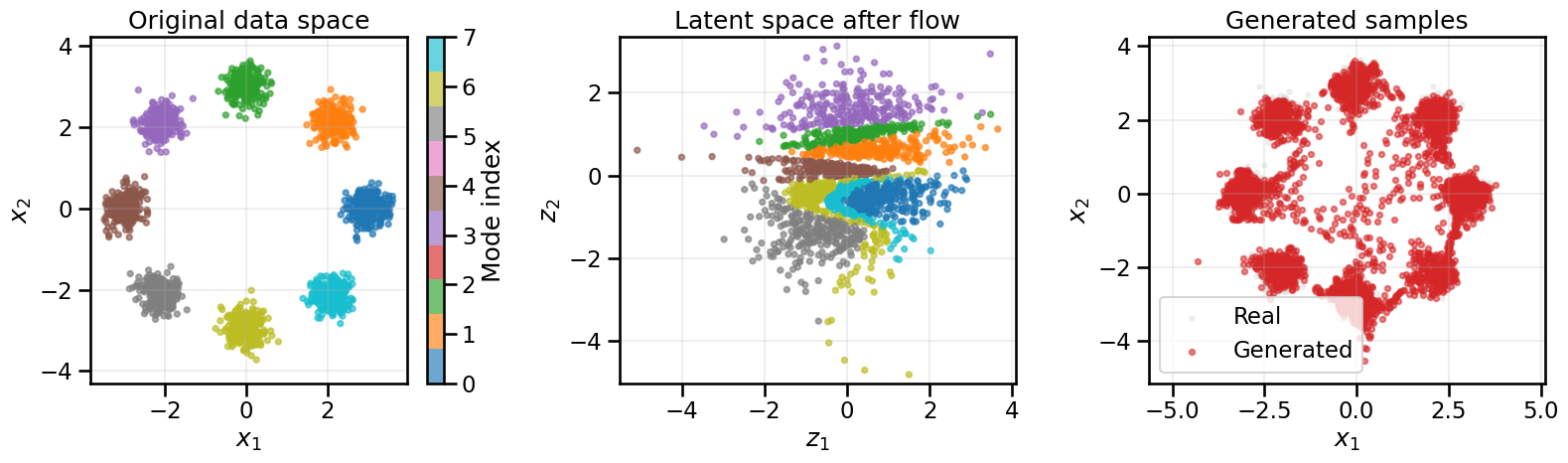

def inverse(self, z: torch.Tensor, y: torch.Tensor) -> Tuple[torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor]:

log_det_total = torch.zeros(z.shape[0], device=z.device)

x = z

for layer in reversed(self.layers):

x, log_det = layer.inverse(x, y)

log_det_total = log_det_total + log_det

return x, log_det_total

def log_prob(self, x: torch.Tensor, y: torch.Tensor, base_dist: MultivariateNormal) -> torch.Tensor:

z, log_det = self.forward(x, y)

log_prob_base = base_dist.log_prob(z)

return log_prob_base + log_det

def sample(self, y: torch.Tensor, base_dist: MultivariateNormal) -> torch.Tensor:

with torch.no_grad():

z = base_dist.sample((y.shape[0],))

x, _ = self.inverse(z, y)

return x

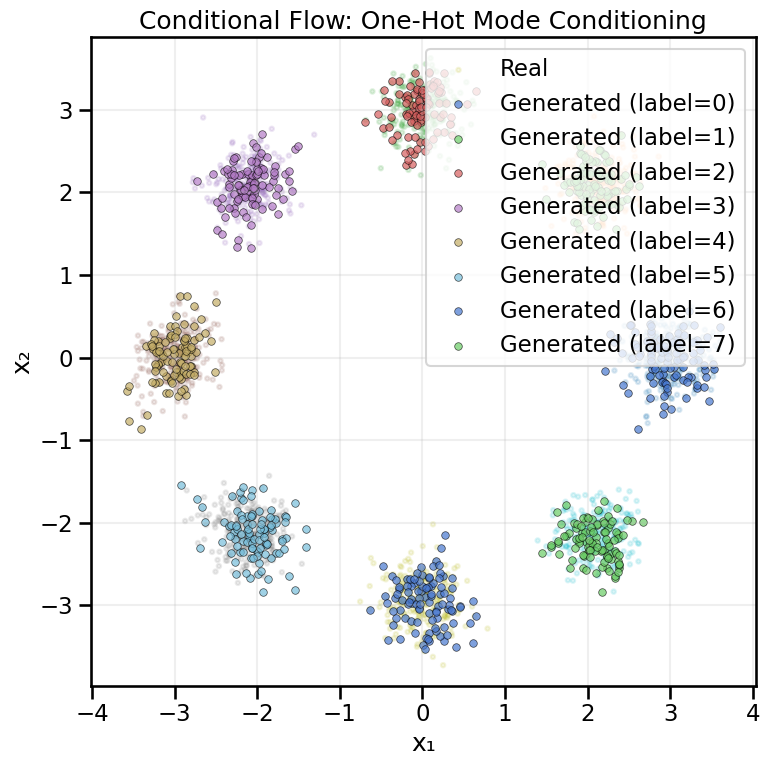

def train_conditional_flow_onehot(

data: np.ndarray, labels: np.ndarray, n_classes: int = 8,

epochs: int = 300, batch_size: int = 256, lr: float = 1e-3, print_every: int = 50

):

loader = make_conditional_loader_onehot(data, labels, batch_size, n_classes)

flow = ConditionalRealNVP(dim=2, cond_dim=n_classes, hidden_dim=128, n_layers=6).to(device)

base_dist = MultivariateNormal(

loc=torch.zeros(2, device=device),

covariance_matrix=torch.eye(2, device=device)

)

optimizer = optim.Adam(flow.parameters(), lr=lr)

history = FlowHistory(loss=[], log_prob=[], diversity=[])

for epoch in range(epochs):

batch_losses, batch_log_probs = [], []

for xb, yb in loader:

xb, yb = xb.to(device), yb.to(device)

log_prob = flow.log_prob(xb, yb, base_dist)

loss = -log_prob.mean()

optimizer.zero_grad()

loss.backward()

optimizer.step()

batch_losses.append(loss.item())

batch_log_probs.append(log_prob.mean().item())

with torch.no_grad():

y_sample = torch.nn.functional.one_hot(

torch.randint(0, n_classes, (2048,), device=device), num_classes=n_classes

).to(torch.float32)

samples = flow.sample(y_sample, base_dist)

diversity = compute_diversity_metric(samples)

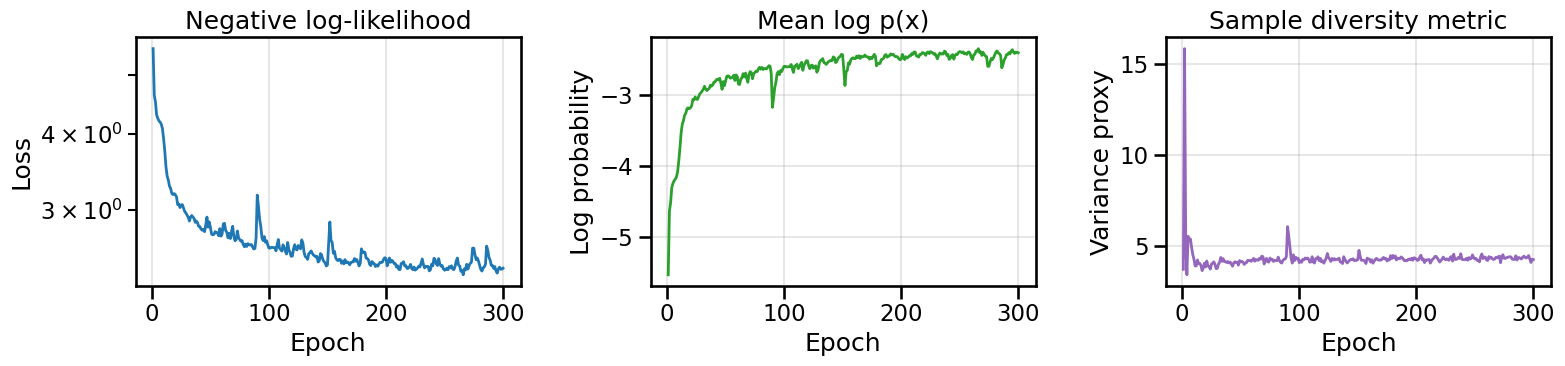

history.loss.append(float(np.mean(batch_losses)))

history.log_prob.append(float(np.mean(batch_log_probs)))

history.diversity.append(diversity)

if (epoch + 1) % print_every == 0 or epoch == 0:

print(f'Epoch {epoch + 1:03d}/{epochs} | Loss: {history.loss[-1]:.3f} | '

f'Log p(x|y): {history.log_prob[-1]:.3f} | Div: {diversity:.3f}')

flow.eval()

return flow, base_dist, history

# Train conditional flow

cflow_onehot, cflow_base_dist, cflow_hist_onehot = train_conditional_flow_onehot(

X_ring, y_ring, n_classes=8, epochs=300, batch_size=256, lr=1e-3, print_every=50

)