# Posterior analysis and visualization

# Sample from posterior

posterior_ro = Predictive(

ramberg_osgood_model,

guide=guide_ro,

num_samples=2000,

return_sites=("E", "sigma_y", "n", "obs"),

)(stresses)

# Extract parameter samples

E_samples = posterior_ro["E"].detach().cpu().numpy()

sigma_y_samples = posterior_ro["sigma_y"].detach().cpu().numpy()

n_samples = posterior_ro["n"].detach().cpu().numpy()

strain_samples = posterior_ro["obs"].detach().cpu().numpy()

# Create summary statistics

print("\n" + "="*60)

print("POSTERIOR SUMMARY STATISTICS")

print("="*60)

print("Parameter | True Value | Posterior Mean | 95% CI")

print("-"*60)

print(f"E (MPa) | {true_E:10.1f} | {E_samples.mean():14.1f} | [{np.percentile(E_samples, 2.5):.1f}, {np.percentile(E_samples, 97.5):.1f}]")

print(f"σ_y (MPa) | {true_sigma_y:10.1f} | {sigma_y_samples.mean():14.1f} | [{np.percentile(sigma_y_samples, 2.5):.1f}, {np.percentile(sigma_y_samples, 97.5):.1f}]")

print(f"n (hardening exp) | {true_n:10.1f} | {n_samples.mean():14.2f} | [{np.percentile(n_samples, 2.5):.2f}, {np.percentile(n_samples, 97.5):.2f}]")

print("="*60)

# Compute predictive statistics

mean_strain = strain_samples.mean(axis=0)

lower_strain = np.percentile(strain_samples, 2.5, axis=0)

upper_strain = np.percentile(strain_samples, 97.5, axis=0)

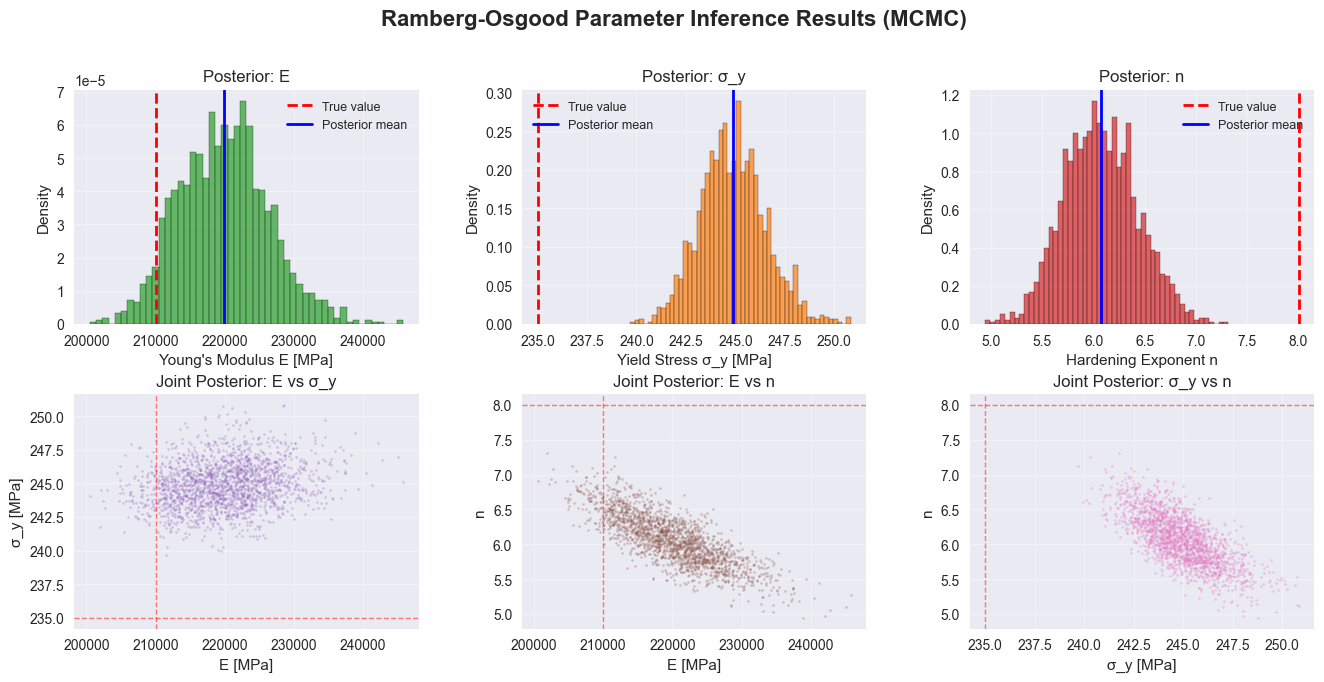

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(16, 10))

gs = fig.add_gridspec(3, 3, hspace=0.3, wspace=0.3)

# 1. Loss curve

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 0])

ax1.plot(ro_losses, color="#1f77b4", linewidth=1.5)

ax1.set_xlabel("Iteration")

ax1.set_ylabel("Per-sample ELBO loss")

ax1.set_title("Training Convergence")

ax1.set_yscale("log")

ax1.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# 2-4. Marginal posteriors

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 1])

ax2.hist(E_samples, bins=50, density=True, color="#2ca02c", alpha=0.7, edgecolor="black")

ax2.axvline(true_E, color="red", linestyle="--", linewidth=2, label="True value")

ax2.axvline(E_samples.mean(), color="blue", linestyle="-", linewidth=2, label="Posterior mean")

ax2.set_xlabel("Young's Modulus E [MPa]")

ax2.set_ylabel("Density")

ax2.set_title("Posterior: E")

ax2.legend(fontsize=9)

ax2.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax3 = fig.add_subplot(gs[0, 2])

ax3.hist(sigma_y_samples, bins=50, density=True, color="#ff7f0e", alpha=0.7, edgecolor="black")

ax3.axvline(true_sigma_y, color="red", linestyle="--", linewidth=2, label="True value")

ax3.axvline(sigma_y_samples.mean(), color="blue", linestyle="-", linewidth=2, label="Posterior mean")

ax3.set_xlabel("Yield Stress σ_y [MPa]")

ax3.set_ylabel("Density")

ax3.set_title("Posterior: σ_y")

ax3.legend(fontsize=9)

ax3.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax4 = fig.add_subplot(gs[1, 0])

ax4.hist(n_samples, bins=50, density=True, color="#d62728", alpha=0.7, edgecolor="black")

ax4.axvline(true_n, color="red", linestyle="--", linewidth=2, label="True value")

ax4.axvline(n_samples.mean(), color="blue", linestyle="-", linewidth=2, label="Posterior mean")

ax4.set_xlabel("Hardening Exponent n")

ax4.set_ylabel("Density")

ax4.set_title("Posterior: n")

ax4.legend(fontsize=9)

ax4.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# 5-7. Joint posteriors (2D scatter plots)

ax5 = fig.add_subplot(gs[1, 1])

ax5.scatter(E_samples, sigma_y_samples, s=2, alpha=0.3, color="#9467bd")

ax5.axvline(true_E, color="red", linestyle="--", linewidth=1, alpha=0.5)

ax5.axhline(true_sigma_y, color="red", linestyle="--", linewidth=1, alpha=0.5)

ax5.set_xlabel("E [MPa]")

ax5.set_ylabel("σ_y [MPa]")

ax5.set_title("Joint Posterior: E vs σ_y")

ax5.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax6 = fig.add_subplot(gs[1, 2])

ax6.scatter(E_samples, n_samples, s=2, alpha=0.3, color="#8c564b")

ax6.axvline(true_E, color="red", linestyle="--", linewidth=1, alpha=0.5)

ax6.axhline(true_n, color="red", linestyle="--", linewidth=1, alpha=0.5)

ax6.set_xlabel("E [MPa]")

ax6.set_ylabel("n")

ax6.set_title("Joint Posterior: E vs n")

ax6.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

ax7 = fig.add_subplot(gs[2, 0])

ax7.scatter(sigma_y_samples, n_samples, s=2, alpha=0.3, color="#e377c2")

ax7.axvline(true_sigma_y, color="red", linestyle="--", linewidth=1, alpha=0.5)

ax7.axhline(true_n, color="red", linestyle="--", linewidth=1, alpha=0.5)

ax7.set_xlabel("σ_y [MPa]")

ax7.set_ylabel("n")

ax7.set_title("Joint Posterior: σ_y vs n")

ax7.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# 8. Posterior predictive on stress-strain curve

ax8 = fig.add_subplot(gs[2, 1:])

# Plot observed data

ax8.scatter(strains.numpy() * 1e3, stresses.numpy(),

s=30, color="#1f77b4", alpha=0.6, label="Observed data", zorder=3)

# Plot posterior mean

ax8.plot(mean_strain * 1e3, stresses.numpy(),

color="#2ca02c", linewidth=2.5, label="Posterior mean", zorder=4)

# Plot credible interval

ax8.fill_betweenx(stresses.numpy(), lower_strain * 1e3, upper_strain * 1e3,

color="#2ca02c", alpha=0.2, label="95% credible interval", zorder=1)

ax8.set_xlabel("Strain [milli-strain]")

ax8.set_ylabel("Stress [MPa]")

ax8.set_title("Posterior Predictive: Stress-Strain Curve")

ax8.legend(loc="upper left", fontsize=10)

ax8.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

plt.suptitle("Ramberg-Osgood Parameter Inference Results", fontsize=16, fontweight="bold", y=0.995)

plt.show()